In this article, we understand What is Patanjali Yoga Sutra? And how it works to benefit in day-to-day life. The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali is a collection of 196 short verses that serve as a guide to attain wisdom and self-realization through yoga. Patanjali is known as the father of modern Yoga. The text is estimated to have been written in roughly the 2nd century BC and is regarded by many as the basis of yoga philosophy. The Sutra offers a strategy for discovering the state of wholeness that already exists in us, and for how we can begin to understand and let go of our suffering. This, he reminds us, is the true aim of yoga.

What is Patanjali Yoga Sutra?

The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, compiled by the sage Patanjali 2nd century BC is considered one of the main authoritative texts on the practice and philosophy of yoga. The Yoga Sutras outline the eight limbs of yoga, which teach us the ways in which one can live a yogic life. It also describes the results of regular, dedicated practice. Yet before any of this, The Yoga Sutras begins by defining the goal of yoga and later goes about describing how one can achieve that goal.

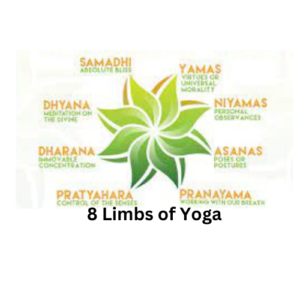

Sutra means “thread,” which describes the relationship of the sutras—they are interrelated or tied together as if by a thread. Within the Yoga Sutras are 196 aphorisms, short passages that guide the reader through four chapters, or books (padas): Samadhi Pada, which describes the results of yoga practice; Sadhana Pada, which describes the discipline itself; Vibhuti Pada, which describes some of the super-normal effects the practice can have; and Kaivalya Pada, which describes the process of liberation of the ego. Let us discuss about 8 limbs of Yoga.

What are the 8 Limbs of Yoga?

- YAMA – Restraints, moral disciplines or moral vows

- NIYAMA – Positive duties or observances

- ASANA – Posture

- PRANAYAMA – Breathing Techniques

- PRATYAHARA – Sense withdrawal

- DHARANA – Focused Concentration

- DHYANA – Meditative Absorption

- SAMADHI – Bliss or Enlightenment

1. YAMA – Restraints, moral disciplines or moral vows

This first limb, Yama, refers to vows, disciplines or practices that are primarily concerned with the world around us, and our interaction with it. While the practice of yoga can indeed increase physical strength and flexibility and aid in calming the mind, what’s the point if we’re still rigid, weak and stressed out in day-to-day life?

There are five Yamas:

- Ahimsa (non-violence),

- Satya (truthfulness),

- Asteya (non-stealing),

- Brahmacharya (right use of energy), and

- Aparigraha (non-greed or non-hoarding).

Yoga is a practice of transforming and benefitting every aspect of life, not just the 60 minutes spent on a rubber mat; if we can learn to be kind, and truthful and use our energy in a worthwhile way, we will not only benefit ourselves our practice, but everything and everyone around us.

In BKS Iyengar’s translation of the sutras ‘Light on The Yoga Sutras’, he explains that Yamas are ‘unconditioned by time, class and place’, meaning no matter who we are, where we come from, or how much yoga we’ve practised, we can all aim to instil the Yamas within us.

2. NIYAMA – Positive duties or observances

The second limb of the 8 limbs of yoga, Niyama, usually refers to internal duties. The prefix ‘ni’ is a Sanskrit verb which means ‘inward’ or ‘within’.

There are five Niyama’s:

- saucha (cleanliness),

- santosha (contentment),

- tapas (discipline or burning desire or conversely, burning of desire),

- svadhyaya (self-study or self-reflection, and study of spiritual texts), and

- isvarapranidaha (surrender to a higher power).

Niyamas are traditionally practised by those who wish to travel further along the Yogic path and are intended to build character. Interestingly, the Niyamas closely relate to the Koshas, our ‘sheaths’ or ‘layers’ leading from the physical body to the essence within. As you’ll notice, when we work with the Niyama – from saucha to is vararpranidhana – we are guided from the grossest aspects of ourselves to the truth within.

3. ASANA – Posture

The physical aspect of yoga is the third step on the path to freedom, and if we’re being honest, the word asana here doesn’t refer to the ability to perform a handstand or an aesthetically impressive backbend, it means ‘seat’ – specifically the seat you would take for the practice of meditation. The only alignment instruction Patanjali gives for this asana is “sthira sukham asanam”, the posture should be steady and comfortable.

While traditional texts like the Hatha Yoga Pradipika list many postures such as Padmasana (lotus pose) and Virasana (hero pose) suitable for meditation, this text also tells us that the most important posture is, in fact, sthirasukhasana – meaning, ‘a posture the practitioner can hold comfortably and motionlessness’.

The idea is to be able to sit in comfort, so we’re not ‘pulled’ by aches and pains or restlessness due to being uncomfortable. Perhaps this is something to consider in your next yoga class if you always tend to choose the ‘advanced’ posture offered, rather than the one your body is able to attain: “In how many poses are we really comfortable and steady?”

4. PRANAYAMA – Breathing Techniques

The word Prana refers to ‘energy’ or ‘life source’. It often describes the very essence that keeps us alive, as well as the energy in the universe around us. Prana also often describes the breath, and by working with the way we breathe, we affect the mind in a very real way.

Perhaps one of the most fascinating things about Pranayama is the fact that it can mean two totally different things, which may lead us in two totally different directions at this point on the path to freedom….

We can interpret Pranayama in a couple of ways. ‘Prana-yama’ can mean ‘breath control’ or ‘breath restraint’, or ‘prana-ayama’ which would translate as ‘freedom of breath’, ‘breath expansion’ or ‘breath liberation’.

The physical act of working with different breathing techniques alters the mind in a myriad of ways – we can choose calming practices like Chandra Bhandana (moon piercing breath) or more stimulating techniques such as Kapalabhati (shining skull cleansing breath).

Each way of breathing will change our state of being, but it’s up to us as to whether we perceive this as ‘controlling’ the way we feel or ‘freeing’ ourselves from the habitual way our mind may usually be.

5. PRATYAHARA – Sense withdrawal

Pratya means to ‘withdraw’, ‘draw in’ or ‘drawback’, and the second part ahara refers to anything we ‘take in’ by ourselves, such as the various sights, sounds and smells our senses take in continuously. When sitting for a formal meditation practice, this is likely to be the first thing we do when we think we’re meditating; we focus on ‘drawing in’. The practice of drawing inward may include focusing on the way we’re breathing, so this limb would relate directly to the practice of pranayama too.

The phrase ‘sense withdrawal’ conjures up images of being able to switch our senses ‘off’ through concentration, which is why this aspect of practice is often misunderstood.

Instead of actually losing the ability to hear and smell, to see and feel, the practice of pratyahara changes our state of mind so that we become so absorbed in what it is we’re focusing on, that the things outside of ourselves no longer bother us and we’re able to meditate without becoming easily distracted. Experienced practitioners may be able to translate pratyahara into everyday life – being so concentrated and present to the moment at hand, that things like sensations and sounds don’t easily distract the mind.

6. DHARANA – Focused Concentration

Dharana means ‘focused concentration’. Dha means ‘holding or maintaining’, and Ana means ‘other’ or ‘something else’. Closely linked to the previous two limbs; dharana and pratyahara are essential parts of the same aspect. To focus on something, we must withdraw our senses so that all attention is on that point of concentration. To draw our senses in, we must focus and concentrate intently. Tratak (candle gazing), visualization, and focusing on the breath are all practices of Dharana, and it’s this stage many of us get to when we think we’re ‘meditating’.

7. DHYANA – Meditative Absorption

The seventh limb is ‘meditative absorption’ – when we become completely absorbed in the focus of our meditation, and this is when we’re really meditating. All the things we may learn in class are merely techniques in order to help us settle, focus and concentrate. The actual practice of meditation is not something we can actively ‘do’, rather it describes the spontaneous action of something that happens as a result of everything else. Essentially; if you are really meditating, you won’t have the thought ‘oh, I’m meditating!’…. (sound familiar?)

8. SAMADHI – Bliss or Enlightenment

Many of us know the word samadhi as meaning ‘bliss’ or ‘enlightenment’, and this is the final step of the journey of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras. After we’ve re-organized our relationships with the outside world and our own inner world, we come to the finale of bliss. When we look at the word samadhi though, we find out that ‘enlightenment’ or ‘realization’ does not refer to floating away on a cloud in a state of happiness and ecstasy…. Sorry.

Breaking the word in half, we see that this final stage is made up of two words; ‘sama’ meaning ‘same’ or ‘equal’, and ‘dhi’ meaning ‘to see’. There’s a reason it’s called realization. It’s because reaching Samadhi is not about escapism, floating away or being abundantly joyful; it’s about realizing the very life that lies in front of us. The ability to ‘see equally’ and without disturbance from the mind, without our experience being conditioned by likes, dislikes or habits, without a need to judge or become attached to any particular aspect; that is bliss.

Conclusion :

We understand What is Patanjali Yoga Sutras? Now we very well know the 8 limbs of Patanjali Yoga Sutras also called “Ashtan yoga” By practicing every day at least 30 to 45 minutes of Yoga Aasan and Pranayama one’s life becomes fit. If you have any doubt please leave comments.

FAQs:

1. What is the meaning of Vritti in Patanjali Yoga sutra?

Ans: Vritti means cyclical movements of energy in the spine. ( 1) In the Yoga Sutras, Patanjali begins: “Yogas Chitta Vritti nirodha,” translated as “Yoga is the neutralization of the vortices of feeling.” Vritti’s are habitual motions of thoughts associated with egoic desires and attachments.

2. What are the 5 Vritti’s of Patanjali?

Ans:

- Correct knowledge (Pramana)

- Incorrect knowledge (viparyaya)

- Imagination or fantasy (vikalpa)

- Sleep (Nidra)

- Memory (Smrti)

3. How many types of pranayama are there in Patanjali?

In Patanjali Yoga Sutras there are four specific types of pranayama:

1.Puraka – inhalation

2. Rechaka – exhalation

3. Kumbhaka – retention of breath after inhalation or exhalation

4. Kevala Kumbhaka – spontaneous and effortless retention of breath after exhalation or inhalation, without any need for inhalation or exhalation.

These four types of pranayama are considered the fundamental techniques, and there are variations and combinations of these techniques that can be used to achieve different effects. It is worth noting that pranayama should always be practiced under the guidance of an experienced teacher .

5 thoughts on “What is Patanjali Yoga Sutra?”